Experts and connoisseurs debate the age-old mystique behind finely-crafted wines that gain complexity and grandeur with longevity

THE CLICHE “aging like fine wine” is a reminder that certain wines have an uncanny ability to gain complexity and grandeur with longevity. But not all wines are created equal, at least not in terms of ability to age in such graceful fashion. According to trade industry statistics, the majority of American consumers pop the cork (or screwcap) on store-bought wine purchases within one to two weeks.

So exactly what defines a “fine” wine? Why does it grow better with age? Is there a proper way to do it, and if so, which wines fare best in the process? To better understand these questions, we talked to winemakers, wine collectors, and wine storage owners about this admittedly highly subjective practice.

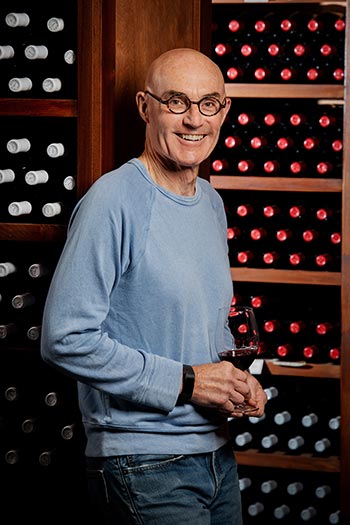

Much of what winemakers do when they produce a bottle of wine is attempt to make that wine somewhat age-worthy. “But, there’s aging, and then there’s aging well,” points out Rick Small, founder and owner of Woodward Canyon Winery, one of the first wineries to open in Walla Walla in 1981.

“If it is done well, one of the great things about wine is that it’s like having children, in that you get to watch them grow up.” Small says that winemakers use any number of different methods and many of them work to produce great aging wine. “For whatever reason, I was just smitten by the European model, probably more of the French white wines like Montrachet, or other white burgundies that are just absolutely beautiful. That really spoke to me.”

“If it is done well, one of the great things about wine is that it’s like having children, in that you get to watch them grow up.” Small says that winemakers use any number of different methods and many of them work to produce great aging wine. “For whatever reason, I was just smitten by the European model, probably more of the French white wines like Montrachet, or other white burgundies that are just absolutely beautiful. That really spoke to me.”

He believes it’s a myth that white wines cannot be aged. “Some of the Alsatian wines like Riesling and Gewürztraminer age so well. It’s a little bit harder to do, but when it’s done, it’s so good.”

Small asserts there isn’t a wrong answer to aging, whether in winemaking or in storage. “It’s very subjective. It’s like art, music or literature and that’s the brilliance of it and it’s why we fall in love with it,” he says.

Small says that wines that taste good right now aren’t necessarily the wines that will age well. “So back then, I could put wines away, and I still have some in the library from that time.” Small added that today, unlike many years ago, most wine critiques are aware of the difference in wines made for immediate consumption, and wines that will last for a few years.

The Karate Kid Method

Len Parris, founder and owner of Chandler Reach Vineyards in the Yakima Valley says, “We use the Karate Kid method here. That means that the wine needs to have balance.” Parris says that for him, the constant battle is making certain that pH and acidity levels are well balanced, and that can be harder than it appears.

“If you have the good fortune of having the vineyard in a very good location, and I knock on wood and pray to whatever wine gods there are, that Chandler Reach is in a very special place, our levels have always been in balance, except for in cold years,” Parris says.

“We pick based on flavor, and usually you find that if the flavor is dynamic, then Mother Nature has found that Karate Kid moment—that balance that makes the flavors pop so well,” adds Parris. He believes in growing wine quality in the vineyard that will translate to a wine that ages well. “Washington has been very good for that, it’s a very special place,” he says.

It’s a well-known adage for winemakers that quality begins and ends in the vineyard, but just why that is so is a more detailed, and yes, a more subjective conversation. Ron Bunnell, owner and winemaker at The Bunnell Family Cellar traces his experience with aging wines back to his education in enology at U.C. Davis. “I learned wine phenolics from Vern Singleton,” Bunnell says. “He spent his entire career trying to shortcut the aging process. He never succeeded, but I learned a lot about phenolics from him and that’s what aging wine is all about.”

Phenolics are phenols and polyphenols, which are made up of hundreds of chemical compounds found in wine that affect its taste, color and mouthfeel. Bunnell says the vagaries of what happens when fermenting juice is introduced to barrels and bottles makes all the difference for each bottle of wine. “I generally release my wines a couple of years after most people do, and I don’t put them in competition until that point,” Bunnell says. “And they seem to do pretty well.”

Bunnell says that while his wines are soft in tannins, they are more extracted, and that allows them to age longer and maintain that balance. “It was my plan all along to age wines, and I still have some in the library from 2004, the year we opened that have that nice brick color around the edge, but follow through on taste and body really well.”

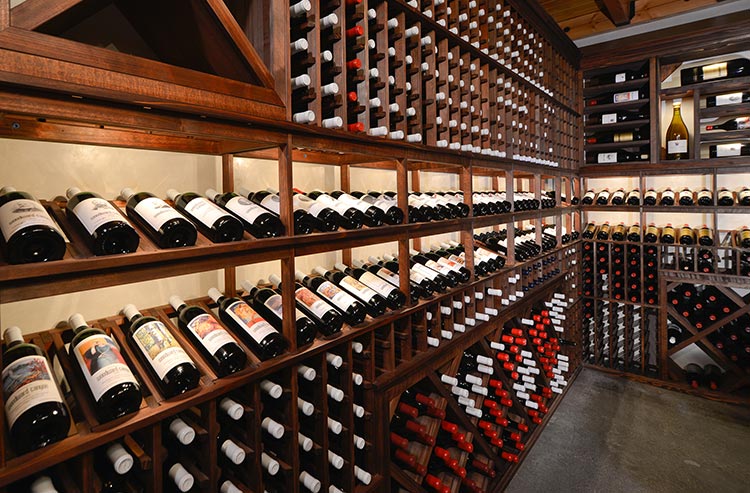

It seems obvious that a well-made wine will age better than one that is made by volume and packaged for the purpose of immediate consumption. But how one stores a wine is just as important. Once you own the bottle of wine, Small says the best place to store it is in a dark place that doesn’t change temperature too radically.

Friends’ Wine Club

Washington Tasting Room Magazine reader Darryl Elves is a wine collector and aficionado who developed a passion for wine when he made trips with a friend to San Francisco in his twenties and began tasting in the Napa and Sonoma Valleys. By chance he met Robert Mondavi and along with his friend, and his friend’s fiance, Mondavi took them into his tasting room and shared a 1959 Cabernet. “I’ve never forgotten. It’s almost like a curse once you’ve tasted something that is so out of the ordinary,” Elves says, adding, “It was a once-in-a-lifetime experience for me.”

Elves and his wife decided they would build a wine cellar in their home so they could begin aging wines. Elves wanted to reconnect with buddies he grew up with and created a friends’ wine club, so to speak. “The premise was there were ten of us friends, split into five pairs. The rules were you had to buy either a 94-point rated wine or $40 bottle (it’s now up to $50) and you had to buy two of each,” explains Elves. “We would taste together, and then I would store five of the bottles away to taste again at a later date.”

The friends’ club holds a tasting each November, and a dinner every summer in which they share the current bottles, the aged bottles, and they go through a series of notes comparing the aged ones after five years of cellaring. The results? “So we’ve seen instances where after five years, and aging at a stable temperature of between 55 and 62 degrees, the wine really improves. But we’ve also seen wine that clearly went downhill in those five years.”

Elves has also encountered wines, like an ‘82 Bordeaux that he says was absolutely incredible. “But then we’d have two or three of the same vintage, though different winemakers, and at first they too tasted wonderful, but within five minutes, it would oxidate and it was no longer pleasant,” he says. “It was the strangest thing—and it opened our eyes to how rare it is for a bottle of wine to make it to 20 or 25 years of storage.”

Professional Storage

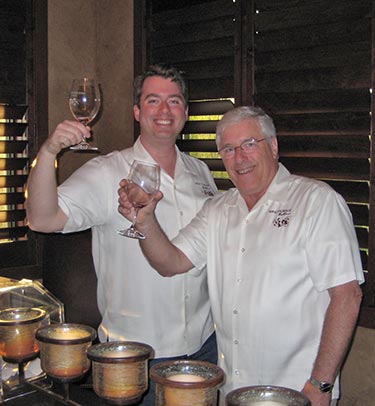

For most wine purchases, aging is merely a process of laying down bottles on a rack in the most temperature neutral room in the house. That might work for a year or two, or possibly even three. But once wine purchases become wine collections, most winemakers and collectors say it’s time to start thinking beyond a simple closet or wine refrigerator. Patrick Gilroy co-owns Wine Storage Bellevue with his father Richard Gilroy. They provide 480 temperature controlled wine lockers, concierge wine delivery service, and a unique tasting room for customers who want to hold private events with the wines they store.

“We provide storage in lockers that go from a six-case space all the way up to 63 cases,” Gilroy says. “Once you get to storage that holds 84, 88 and 96-cases, those are walk-in units where most people put racking on the sides and such.” All the units are temperature and humidity controlled and secure, and 24-hour access is provided. In addition, customers have access to a private Tuscan-styled event space called the Amoroso Room, as well as other services like wi-fi.

“If you’re thinking about laying down wine, don’t just buy a bottle and lay it down,” Gilroy says. “Give yourself three or four bottles, or a case if you can afford it, and put all that down and give yourself an opportunity to taste it over time and understand the changes that the wine is going through.”

Written by Mark Storer