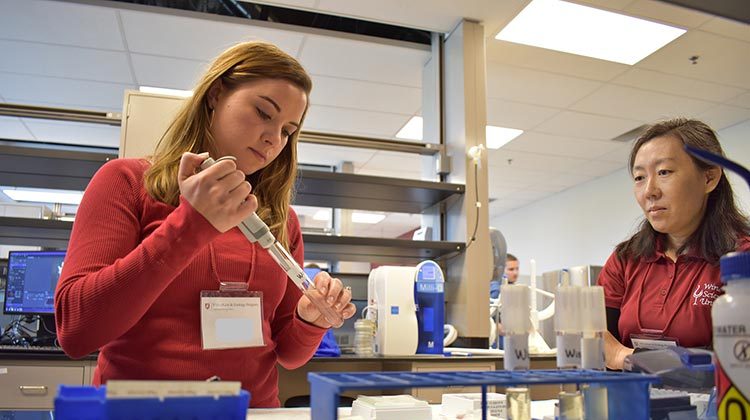

The Wine Science Center is a teaching and research facility where students rub shoulders with some of the brightest research minds in the state

FOR DECADES California wineries have benefited from a “secret weapon”— known as the viticulture and enology program at UC Davis—so powerful that its heroic feats almost read like something out of a Marvel comic book: defeating hordes of vine-eating bugs and villainous creepy-crawlies; protecting grapes from deadly sunburn and suffering; ultimately saving the population from swilling cheap plonk and being plunged into eternal darkness. And now, Washington has its own superhero.It’s called the Wine Science Center in Richland, a new teaching and research facility and long-anticipated addition to Washington State University’s Viticulture and Enology program (V&E). Think of it as a giant laboratory working for the betterment of Washington’s entire wine industry. And it’s filled with some of the world’s most technologically advanced equipment—and brainiest minds—to get the job done.

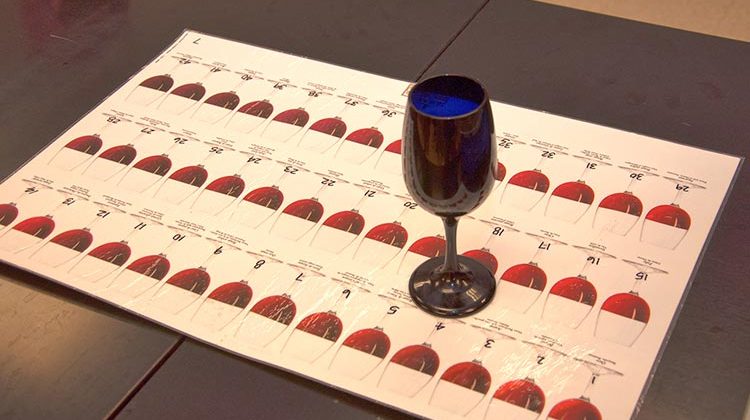

There’s a research and teaching winery where they conduct mind-boggling experiments, research labs, and a two-acre vineyard. Special classrooms have been designed for wine sensory education. There is even a hermetically sealed, odor-free room used for advanced aroma testing, where black-opaque wine glasses ensure unbiased sight-free analysis of wine.

Invaluable Resource

Thomas Henick-Kling, PhD, a native of South Germany, heads up the V&E Program [see page 66 for more about Thomas]. He studied microbiology at Oregon State, and later wine microbiology at Australia’s Wine Research Institute before ending up at Cornell University doing extensive wine research and education.

“We put all our needs together, and it came down to building a facility that provides all the resources for all the research we were not currently doing, and a space for the students and faculty to do the work,” he says of the new center.

According to Henick-Kling, the wine industry needs more trained people at every level. “We have a 98% placement rate, and in some years it is 100%, so the demand for graduates is very high,” he says.

Megan Davis, an enologist at Purple Star Wines in Benton City, graduated from the V&E Program in 2016. “The wine science program at WSU helped set me up for success within the wine industry through advanced education, hands on experience, and quality professional relationships,” says Megan. She adds that a big benefit is the continued support from professors and staff who act as an invaluable resource.

Charlie Lybecker, owner and winemaker of Cairdeas Winery in Chelan, agrees. “The WSU wine science research center is an amazing resource for the Washington wine industry. Their staff have dedicated their careers to advancing methods and techniques that we all use in the cellar everyday,” he says. Lybecker appreciates that he can call on researchers for suggestions or advice anytime he needs.

The Ste. Michelle Wine Estates WSU Wine Science Center is a breath of fresh air for the local wine grape growers and winemakers who rely on advancements in their fields to ensure their grapes and ultimately, the wines, are among the world’s best.

Charlie Lybecker recently attended a WAVEx conference at the Wine Science Center. “It’s a great gathering space for members of the industry,” he says. Washington Advancements in Viticulture and Enology seminars (WAVEx) are one way to put the latest research findings into the hands of growers and vintners.

Bugs, Disease & Viruses

Viticulturist Rick Hamman oversees farming of about 1,200 acres of vineyards at Hogue Ranches in Prosser. “The Wine Science Center is becoming the center for the V&E Program,” he asserts. Hamman is chairman of the Wine Research Advisory Committee, a sub-committee of the Washington Wine Commission, the group responsible for recommending which of WSU’s projects receive industry funding.

The Wine Science Center is still in its infancy—the facility is practically brand new and more funding is needed before it can reach full potential. Yet Hamman points to the huge body of critical research being conducted by the V&E Program. “They are doing important projects that help the industry,” he says. “Disease. Bugs. Viruses. We are covering all the bases that we can with the amount of monies that we have.”

A common disease in Washington is powdery mildew, which can drastically reduce vineyard yields and lower wine quality if not properly treated. Much research has been done and more is in the works, arming growers with necessary tools to treat the disease.

On another front, researchers are surveying Washington vineyards for grapevine red blotch, a virus that has spread extensively among California vineyards but has not yet been a major issue in Washington. Researchers here suspect that a plant-sucking insect carries the virus from plant to plant but so far do not have positive I.D. on the culprit. “We are trying to find out how much red blotch is out there and which insects are vectoring [absorbing and transmitting] it,” says Hamman. “We’ve got to stay vigilant with our testing and making sure that if we do get it, it gets rubbed out and doesn’t spread radically in our state like in California.”

One of the biggest projects taking place is learning about virus impact on the vines. Leafroll is a type of virus that can disrupt the flow of nutrients to the vine, resulting in a lack of flavor ripeness in the fruit—think green bell pepper flavors. Growers have been battling leafroll for years and there is no cure. “We are still learning about the genetics behind it. For example, why is it visible in red grapes and not clearly visible in white grapes?” says Hamman.

Part of the leafroll virus testing includes rearing mealy bugs in a greenhouse environment, which Hamman assures is “harder to do than to talk about.”

Wildfire Smoke & Smart Phones

Local vineyards are occasionally inundated with smoke drifting over from a wildfire area or carried in by the jet stream from fires blazing in Oregon or British Columbia. Scientists are attempting to analyze how smoke affects the quality of the grape after it absorbs into the berry. They hope to provide growers with enough parameters to offer a protocol, whereby growers could take smoke exposed grapes to a lab to determine if there will be any problems making wine.

With so many research projects on the drawing board, possibly one of the more exciting is the development of a smart phone app that would allow growers to estimate crop yields. Photos of vine clusters might someday be sent to the “cloud” where mathematical logarithms would crunch the numbers and return a detailed estimate back to the grower—long in advance of harvest.

Vineyard to Glass

Another major area of research is phenolics—the chemical compounds that affect the color, taste, and texture of wine, such as tannins. In red grapes, many of the phenols are derived from the skin, seeds and stems. “How does the fruit ripen, how are these flavors formed?” poses Henick-Kling, underscoring that a lot of questions are related to vineyard management.

“But then also, there’s always the question: how does that impact the final wine quality?” he says knowingly. “That’s why we built this large research and teaching winery—so we can make all these wines for various purposes, and analyze them and show the wines to the industry and say, if you do this in the vineyard that’s the effect you will get in your wines.”